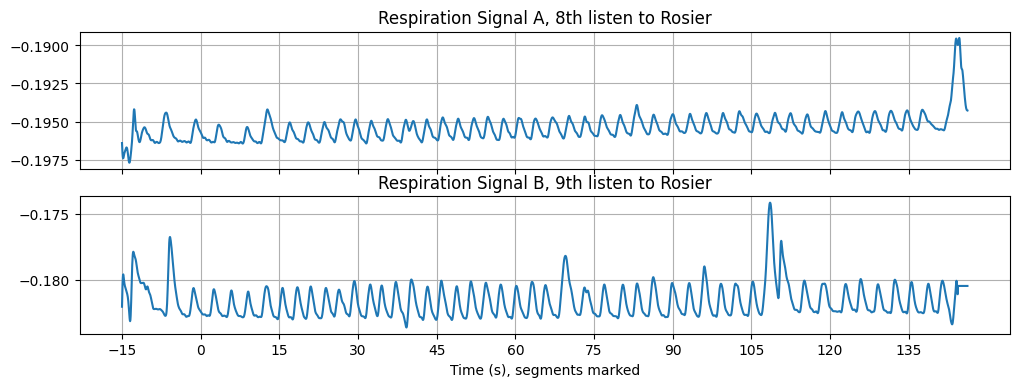

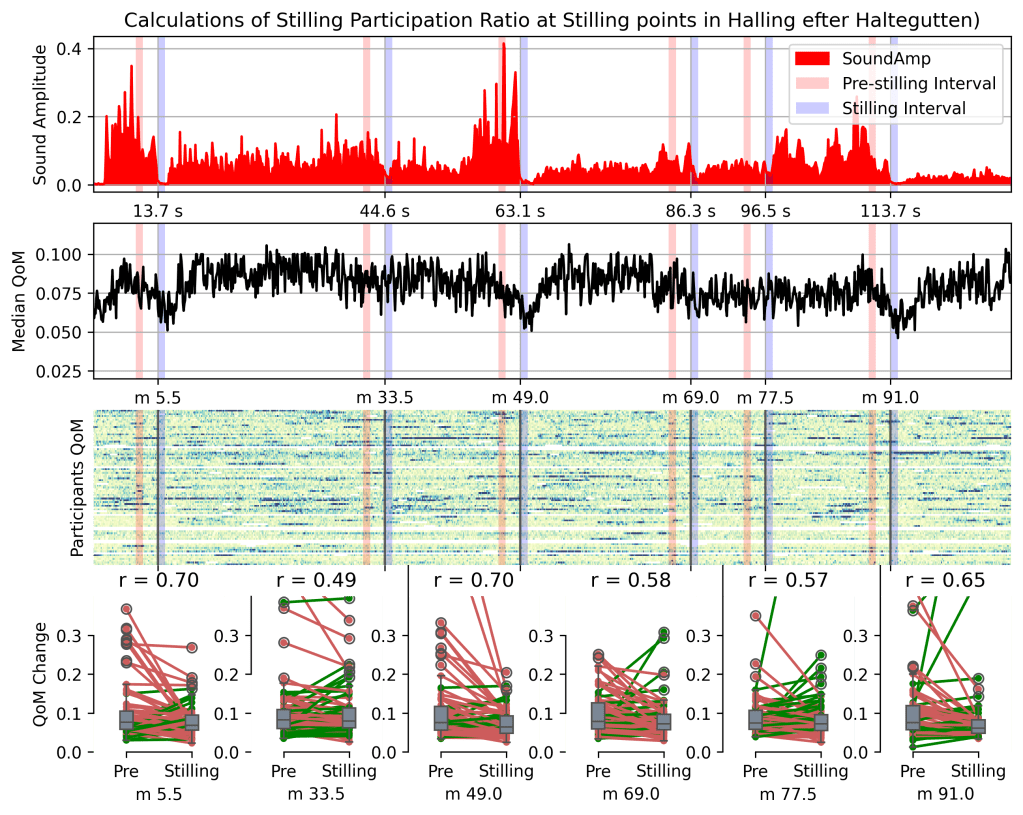

Most of the time, when we are looking for a connection between music and how people move, the focus in on the movement: when the beat drops, when the feet start tapping, when people start to sway. In the Music Lab Copenhagen concert experiment, we found some of that (paper forthcoming) but more strikingly, we also found that audience members seem to move LESS at specific moments of the music. During the Danish String Quartet’s world class performances of music by Beethoven, Schnittke, and Bach, the audience didn’t move with any kind of regular pulse but they instead seem to still for the rests, the drops in texture, and the quiet parts.

After noticing a few of these short dips in average audience motion, we chose to test a hypothetical relationship between the music and the audience’s lack of motion by starting from the performance. Watching it back, could we identifying when the music might encourage stillness? I spent many hours with the music scores, audio, and video to try to get a feeling for what could be a cue for stilling. After a few rounds, criteria for “stilling points” were defined with easily tracked musical surface features. Focusing just on local qualities, just the last few seconds of music, Stilling points were marked with decreases in the number voices (down to full rests), decreases in loudness, decreases in tempo, and silences not indicated in the score. These kinds of moments are common in concert music, but how they show up varies a lot. Rests can be part of a musical theme, returning over and over, while points of repose are subverted in forms like the fugues. Working through the more classical concert repertoire and the concerts closing set of nordic folk song arrangements, I identified from the music 257 Stilling points.

These Stilling points were tracked back to the audience motion measurements (chest mounted accelerometers, collected mostly through a phone app) and tested for the ratio of participants showing less quantity of motion than three seconds before. This very simple metric of collective stilling should normally be around 0.5, with half this mostly-still audience moving marginally more than 3 seconds before and half moving marginally less. But at most of the stilling points, we found that more audience participants were more still than should happen by chance.

The full description of how this assessment and some subsequent evaluations of what cues mattered and how still this audience really got can be found in the Music & Science paper: